KN Magazine: Articles

The Junkman Cometh and Sometimes He Writeth / Author Guinotte Wise

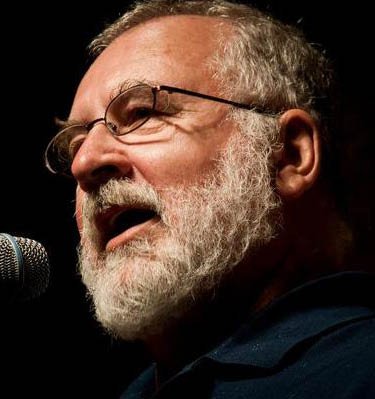

Respect your readers, don’t cheat, cut when necessary, and by all means, keep going. I’ve never met this week’s guest blogger artist and author Guinotte Wise, but after reading this blog, I like him. A lot. Not only is he a good writer, he’s a heck of a welder. Nothing would make me happier than seeing a piece of his art and his collection of short stories sitting side-by-side on my office shelf. I’m a bit of a junkyard dog myself.

Happy Reading!

Clay Stafford,

Founder Killer Nashville,

Publisher Killer Nashville Magazine

The Junkman Cometh and Sometimes He Writeth

By Guinotte Wise

That third person, man, you can get away with anything. It is rumored that Guinotte Wise came within a hair of winning the coveted … The award-winning sculptor and writer has just written a screenplay that some say … The former adman, who during his career won enough chrome and lucite industry awards to make three Buicks …

Snap out of it, Wise. Okay. Junkyards. I’ve loved them since I was a speed-obsessed kid with ducktails, a loud Ford and a smart mouth. Row upon row of decaying cars, some no longer in production, baking, fading in the summer sun. Smells of solvents, grease, gasoline, burnt rubber, and those unidentifiable odors peculiar to junkyards drifting like the turkey buzzards in the cloudless Missouri sky. Maybe that’s why I started welding steel and writing stories. I inhaled that stuff and it made me odd. But it’s my odd and I like it fine.

I have my own junkyard now, and no beady-eyed, bearded old fart in overalls to follow me around, making sure I don’t pocket a carburetor float or a chrome nutcap.

And if, when I’m writing, I get stuck, I go weld. And vice versa. They’re both fugue activities when I’m holding my mouth right and the coffee isn’t burned.

I don’t just stick stuff together when I weld. I’m represented by some galleries, and have solo shows. I’m serious about the writing, too. It’s just that I do what I want. No formulas, no rules, other than this: If I make something and it’s for others, not just myself, respect those people, give them credit for having probably more operating brain cells than I do, and some taste.

I had a horse named Mighty Mouse who passed away this spring. He’s buried on the place. He was a superb athlete in his day and a legendary horseman in his 90’s said of him, “He never cheated me.” From this guy, it was high praise. I would like readers and art buyers to say the same of me, and more, if they’re not blessed with his laconicism. I’d like them to be pleased. Never cheated.

So junkyards and welding and plasma cutting are metaphorically handy in this blog, which is aimed at writers and readers. The junkyard of my mind is cluttered with rows and rows of materials, ready to form new combinations. I’m not being enigmatic when I say of writing, or welding, it happens in the process. I may start out to weld a horse, and a horse happens, but I have no idea what that horse will look like as I construct a frame, an armature, and begin to give it form.

I wrote a book that way, and my agent liked it. No publishers have clamored for it yet, but who knows. I was putting together sculptures for a show the first of this month, and one piece drew a puzzled look from my wife. She didn’t care for it. I have a lot of respect for her opinion, art-wise and lit-wise—she reads a lot, and makes exquisite jewelry—so I left that piece out for a while.

At the last minute, I took it to the gallery and during the show, I was told it was the favorite of some whose opinion I also respect. Go figure.

I think I’m saying here, when you get rejections, have enough faith in your piece to keep submitting it. Your work is not for everyone. If it is, well, maybe you’ll be a bestseller and more power to you. And if, in your reading, you’re fifty pages in and you hate what you’re reading, toss it. Give it to someone else and they may love it.

The plasma cutter. Great when I need it for making things fit. But I sure hate to look at a big piece and realize I made a major error by welding something that doesn’t belong. The cutter comes into play, and not in an enjoyable way. But very necessary if the final form is to be pleasing: to me, to the viewer. Guess where that not very slick allusion fits in the writing process. I hate to cut, steel sculpture or the printed word. But it sometimes needs to be done.

When the rejection comes and they say, as they so often do, “unfortunately your work wasn’t the right fit for this issue,” (I just picked that up word for word from a rejection I got minutes ago) it could mean just that, or it could mean why the hell are you sending us this crap. Or, heat it up and refashion it some. Or write something new altogether. Roam the junkyard. It’s there somewhere.

If you would like to read more about Guinotte Wise’s books please click here.

Guinotte Wise has been a creative director in advertising most of his working life. In his youth he put forth effort as a bull rider, ironworker, laborer, funeral home pickup person, bartender, truck driver, postal worker, icehouse worker, paving field engineer. A staid museum director called him raffish, which he enthusiastically embraced, (the observation, not the director). Of course, he took up writing fiction. He was the winner of the H. Palmer Hall Award for short story collection, “Night Train, Cold Beer,” earning a $1000 cash grant and publication of the book in 2013, Pecan Grove Press. His works have appeared in Crime Factory Review, Stymie, Telling Our Stories Press Anthology, Opium, Negative Suck, Newfound Journal, The MacGuffin, Weather-themed fiction anthology by Imagination and Place Press, Verdad, Stickman Review, Snark (Illusion), Atticus Review, Dark Matter Journal, Writers Tribe Review, LA, The Dying Goose, Amarillo Bay, HOOT, Santa Fe Writers Project, Prick of the Spindle, Gravel Literary Journal, and just had a story accepted in Best New Writers Anthology 2015. Wise is a sculptor, sometimes in welded steel, sometimes in words. Educated at Westminster College, University of Arkansas, Kansas City Art Institute. Tweet him @noirbut. Some work is at http://www.wisesculpture.com/

(Have an idea for our blog? Then share it with our Killer Nashville family. With over 24,000 visits monthly to the Killer Nashville website, over 300,000 reached through social media, and a potential outreach of over 22 million per press release, Killer Nashville provides another way for you to reach more people with your message. Send a query to contact@killernashville.com or call us at 615-599-4032. We’d love to hear from you. Thanks to Maria Giordano, Will Chessor and author Tom Wood for his volunteer assistance in coordinating our weekly blogs. For more writer resources, visit us at www.KillerNashville.com)

A Cozy, Little Success Story 33 Years in the Making / Author Rosalyn Ramage

Sometimes an idea needs time to mature, or in the case of this week’s guest blogger Rosalyn Ramage, the idea needs to find a genre. I think most authors would agree that stories have to come out one way or another. How they are received is another matter. Ramage explains how her latest book took 33 years to see the light of day.

Happy Reading!

Clay Stafford,

Founder Killer Nashville,

Publisher Killer Nashville Magazine

A Cozy, Little Success Story 33 Years in the Making

By Rosalyn Ramage

It’s a done deal! Millicent’s Tower, Five Star Publishing, 2014. Mission accomplished! But wait a minute, I thought as I sat gazing at the book in front of me. Where did you come from, Millicent? Where have you been? What took you so long to get here? Memories began to flutter in . . .

The year was 1980. I had just received my college degree at Belmont College as an older student with children at home. During that time I had been fortunate enough to do some freelance writing, including the publication of two books of children’s poetry. I was on a roll!

Then, in 1981 our family went on vacation to Campobello Island in New Brunswick, Canada, just across the causeway from Lubec, Maine. We were there for a month, and while there, I wrote a book!

Actually, the main plot of the book had been floating around in my head for a while. I had had situations and characters in mind, but no specific names. As we had embarked on the trip, one of our pastimes was to create names for characters that would be in my book. We named them for places and signs that we saw along the way (like Moose when we saw a “Moose crossing” sign).

I had taken my manual typewriter and a ream of paper with me. My writing space was a small room at the back of the cottage with a fantastic view of Passamaquoddy Bay, looking toward Lubec. It was in that setting that Who? came into being. What, you might ask, is Who? That was the title I first gave my book. I called it Who? . . . as in “whodunit.”

Believe it or not, I accomplished my goal and returned to Nashville with a three-ring binder filled with pages for my book. After sharing it with friends and relatives, I met a literary agent who took a look at it. He reviewed the manuscript and returned it to me, saying, “I like the book, but, quite frankly, I don’t quite know what to do with it. It is family-centered, with children, but with adult topics and situations, like . . . dead bodies and . . . ‘language.’ ” He wished me well. All of this was in 1981.

My reaction to this rejection was to take it to my office, put it on a shelf, and forget about it. Life went on.

Then, 29 years after I had given up on my novel, my oldest grandson, who was in college, brought up the topic of Who? He said, “I’ve always heard people talk about Who? But I’ve never seen it myself. Could I read it sometime?”

Hmmmm. Let me see now. Just where had I dumped that dusty, musty manuscript so many years ago? Ah, yes. Here it is. I pulled it out, dusted it off, began to read … and I liked it. As a matter of fact, I liked it so much, I retyped it, added more characters and material, extended the storyline, and dared to ask for a critique at a conference of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) in the fall of 2011.

The gist of what my critiquer said was that she “really liked the story, but didn’t quite know what to do with it.” Sound familiar? It really wasn’t a hard-core adult book, she said, but it certainly wasn’t a children’s book. Young adult? Maybe.

And then she said the magical words: “I think what you have here is a cozy mystery.”

“A what?”

“A cozy mystery,” she said. Hmmm.

In my quick research on cozy mysteries, I found that my book had all of the attributes of a cozy mystery.

I was intrigued. So intrigued, in fact, that I signed up to go to another conference known as Killer Nashville, an annual conference geared especially for writers or would-be writers of various kinds of thrillers, mysteries and suspense.

Long story short, I decided to “pitch” my manuscript and, to my surprise, was asked by an editor at Five Star Publishing to submit my full manuscript for review. After a bit more preening, I submitted Who?, which, by now, had been renamed Millicent’s Tower.

And, in January 2013, I was informed by the editors at Five Star that they would take pleasure in publishing my book.

A long journey for a cozy mystery? You bet. But one I have enjoyed creating at every uncertain step of the way. I sincerely hope other writers will find my story encouraging as they pursue the journey for themselves.

If you would like to read more about Rosalyn Ramage’s books please click here.

Rosalyn Ramage is the author of two books of children’s poetry entitled A BOOK FOR ALL SEASONS and A BOOK ABOUT PEOPLE. She is also the author of three middle grade mysteries entitled The TRACKS, The GRAVEYARD, and The WINDMILL. She is a retired elementary school teacher who enjoys writing poems and stories for readers of all ages…just for the fun of it! MILLICENT’S TOWER is her first book for a more mature audience. She and her husband Don split their time between their farm in Kentucky and their home in Nashville, Tennessee. She invites you to visit her website at rosalynrikelramage.weebly.com.

(Have an idea for our blog? Then share it with our Killer Nashville family. With over 24,000 visits monthly to the Killer Nashville website, over 300,000 reached through social media, and a potential outreach of over 22 million per press release, Killer Nashville provides another way for you to reach more people with your message. Send a query to contact@killernashville.com or call us at 615-599-4032. We’d love to hear from you. Thanks to Maria Giordano, Will Chessor and author Tom Wood for his volunteer assistance in coordinating our weekly blogs. For more writer resources, visit us at www.KillerNashville.com)

Thrills and Chills: Teaching the Art of Suspense Writing to Kids / Author Kimberly Dana

There is a line in the rock opera “Evita” where the narrator Che’ says with equal parts accusation and admiration, “Get them while they’re young, Evita. Get them while they’re young,” which is to say grow your ranks. In this week’s guest blog, author Kimberly Dana isn’t building a dictatorship; she’s growing young minds to become book lovers and writers with the art of suspense. I was fascinated with her technique…and learned a great deal myself.

Read like they are burning books!

Clay Stafford,

Founder Killer Nashville,

Publisher Killer Nashville Magazine

Thrills and Chills:

Teaching the Art of Suspense Writing to Kids

By Kimberly Dana

Kids adore the adrenaline rush, so it is no surprise they have an innate attraction to the genre of suspense. The feelings of tension, uncertainty, doubt and apprehension all parallel the angst of adolescence, resulting in a familiar emotional connection. Additionally, the physiological response of the pounding beating heart, the spine-prickling shivers, and mind-buzzing thoughts serve up an intoxicating thrill ride kids thrive on.

Consequently, it makes perfect sense that kids make amazing suspense writers — if given the proper tools.

What are the benefits of teaching suspense writing to kids?

1) Adults want to be glued to the page and kids are no exception — only “the hook” is even more critical in their techno world of iPad, iPod, and iPhone instant gratification (Clearly, this is what the “i” must stand for)! So as teachers, we have our work cut out for us; however, if boredom is the archenemy of a love for literacy, then suspense is the antidote. Suspenseful stories have universal appeal and can magically pique the interest of even the most reluctant of readers, jarring them awake from their ill-fated K-12 “School-is-boring. Reading is stupid” stupor. A story whereby an ordinary person is thrown into extraordinary circumstances is irresistible. Throw in a ticking clock and a spooky setting, and you just made Jaded Johnny a lifetime reader. Talk about a best practices with synergistic effects!

2) To strengthen our resolve in making book buffs out of reluctant readers, suspenseful stories contain rich literary elements including dark, villainous characters; mysterious motifs of staircases, woods, graveyards, shadows, and confined spaces; and, thought-provoking thematic subjects, such as perception versus reality, good over evil, and isolation and imprisonment. Suspense stories are not only an entertaining vehicle, they surreptitiously breed critical thinking and deductive reasoning skills from students whom are not otherwise be engaged.

3) Finally, suspenseful stories empower kids by unmasking the cerebral tools and coping skills needed in order to tackle life’s enigmas. Through exposure to mysterious worlds of dark characters and thematic messages, kids learn to revere intelligence, sagacity, and fearlessness. Kids love to “get deep” as they debate and argue over the finer points of plot. Insulated by a safe, voyeuristic lens, kids can safely unravel intricate storylines as they earnestly judge the innocent versus the guilty, thereby refining their own sense of morality. What’s more, suspenseful stories generate rich discussion in literary analysis and are a perfect springboard for developing kids’ own unique writing craft and style.

So how do we teach suspense? The first thing we have to teach kids is what suspense is: A state or feeling of excited or anxious uncertainty about what may happen as opposed to what suspense is not: Suspense is not horror. The two are easily confused so when I introduce the concept, I always translate it into kid-speak. I tell my students, “Suspense is not Freddy Krueger or Michael Myers. It is much more refined than blood and gore. And therefore, even more terrifying.”

“What is the difference?” they ask with bated breath.

“It’s simple,” I tell them. “Horror shows. Suspense implies. And then I dim the lights, set match to a votive candle, and read Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart.” And when the narrator tears up the planks and proclaims, “Villains…dissemble no more! I admit the deed! — tear up the planks! — here, here! — it is the beating of his hideous heart!” — I look out into their shiny eyes, burning brightly and begging for more. So later that week we read suspense-riddled tomes, such as “The Monkey’s Paw,” “Lamb to the Slaughter,” and “The Lottery.”

Once my students are feeling creatively juiced with sordid secrets, villainous vendettas, gothic graveyards, and are up to the task of writing their own stories, it is my modus operandi to get them past “It was a dark and stormy night..."

This is, of course, how most kids will begin their suspense story. Not that there is anything wrong with dark and stormy nights. Dark and stormy nights are a perfect setting when building a backdrop for suspense. But in the interest of avoiding clichés, I front-load my kid writers to a special acronymic formula for “writhe-in-your-seat-worthy” suspense writing: G.E.M. — Gothicism, Expansion of Time, and Magic of Three.

GOTHICISM: All suspense stories should express an element of the gothic genre, such as the supernatural; an eerie, mysterious setting; emotion over passion; or distinctive characters who are lonely, isolated, and/or oppressed. Throw in a tyrannical villain, a vendetta, or an illicit love affair — you've got Goth gold! Why Gothicism? It explores the tragic themes of life and the darker side of human nature. What’s more, kids innately are attracted to it. Just ask Stephenie Meyer.

EXPANDING TIME: Next, I introduce the art of expanding time using foreshadowing, flashback, and implementing “well, um...maybe…let me see” dialogue.” Expanding time allows the writer to twist, turn, and tangle up the plot. “Tease your audience,” I tell my students. “Pile on the problems and trap your protagonist with a ticking clock. Every second counts with suspense!” There is an old writing adage that says to write slow scenes fast and fast scenes slow. By delaying the big reveal, we build tension and punch up the plot.

MAGIC OF THREE: Finally, the Magic of Three comes into play. The Magic of Three is a writer's trick where a series of three hints lead to a major discovery. During the first hint, the protagonist detects something is amiss. The second hint sparks a more intense reaction, but nothing is discovered — yet. And then — BANG! The third hint leads to a discovery or revelation. During the big reveal, I teach kids to use and manipulate red flags and phrases, such as Suddenly, Without warning, In a blink of an eye, Instantly, A moment later, Like a shot, To my shock, and To my horror.

Teaching suspense writing to kids breeds amazing results. Once they learn to tantalize their audience through the craft of anticipation with G.E.M., they recognize the power behind suspense and why audiences are drawn to the genre. More importantly, they appreciate suspense for what it is...the secret sauce of writing.

“So go mine your story, and find your G.E.M.,” I tell my students. “The clock is ticking...”

If you would like to read more about Kimberly Dana's books please click here.

Featured on NBC’s More at Midday and The Tennessean as a middle school tween expert, Kimberly Dana is a multi-award-winning young adult and children's author. She is published by the National Council of Teachers of English, Parenthood, Your Teen, About Families, SI Parent, Sonoma Family Life, and the recipient of several writing honors from Writers Digest, Reader Views, the Pacific Northwest Writer Association, and various international book festivals. Other affiliations include the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators and EPIC, the Electronic Publishing Industry Coalition, where she serves as a judge for the annual eBook competition. Kimberly’s most recent books include her YA thriller, Cheerage Fearage, middle grade novel Lucy and CeCee’s How to Survive (and Thrive) in Middle School, Pretty Dolls, voted Best Children’s Book of the Year by Reader Views and Character Building Counts, and Buon Appetito, a children’s picture book that celebrates diversity and the English Language Learner published by Schoolwide Inc. Kimberly has been endorsed by Common Core News and a featured presenter at the Southern Festival of Books, The Carnegie Writers Group, Killer Nashville Writers Conference, and schools nationwide. A lover of photography and experimental cooking, Kimberly lives in Nashville with her husband and spoiled Shih Tzu. Visit her website at http://kimberlydana.blogspot.com

(Have an idea for our blog? Then share it with our Killer Nashville family. With over 24,000 visits monthly to the Killer Nashville website, over 300,000 reached through social media, and a potential outreach of over 22 million per press release, Killer Nashville provides another way for you to reach more people with your message. Send a query to contact@killernashville.com or call us at 615-599-4032. We’d love to hear from you. Thanks to Maria Giordano, Will Chessor and author Tom Wood for his volunteer assistance in coordinating our weekly blogs. For more writer resources, visit us at www.KillerNashville.com)

Natural Born Writers, Ready Made Stories: Writing and the Law / Author Robert Rotstein

The legal system abounds with conflict, quirky characters, mystery, and moral ambiguity. This is why writers tend to draw often and steadily from this familiar well, says author Robert Rotstein. This week’s guest blogger, Rotstein spells out why writers, many of them lawyers, find inspiration at the courthouse.

Happy Reading! And until next time, read like someone is burning the books.

Clay Stafford,

Founder Killer Nashville,

Publisher Killer Nashville Magazine

Natural Born Writers, Ready Made Stories:

Writing and the Law

By Robert Rotstein

Stories about the legal system abound and have for centuries. There are novels, some of them classic works of literature, like Charles Dickens’s Bleak House, Herman Melville’s Billy Budd the Sailor, Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, John Grisham’s A Time to Kill, and Scott Turow’s Presumed Innocent. There are great movies, like 12 Angry Men, The Verdict, Philadelphia, and A Few Good Men. And there are the long-running TV shows: Perry Mason, L.A. Law, Law & Order, The Good Wife.

Not only do authors write about the law, but many lawyers have become authors. Henry Fielding, Wallace Stevens, and Franz Kafka had legal backgrounds, as do thriller writers Grisham, Turow, Steve Berry, and Lisa Scottoline, among many others. I’ve written two legal novels and still practice law full time.

If you accept the stereotypes, writers and lawyers are nothing alike. Attorneys are supposedly combative, social, linear thinkers. Writers are imaginative, introspective loners. So why are fiction writers fascinated with the legal system? And why have so many lawyers become successful writers? I believe it’s because lawsuits are real-life dramas.

The most basic piece of advice that aspiring writers hear at workshops in seminars is that the story has to create conflict. Lawsuits are all about conflict. The legal system is set up that way—it’s an adversarial system, and where there are adversaries, there are stories. Take the most basic slip-and-fall lawsuit. The plaintiff says he fell on a banana peel in the supermarket-produce section. The store manager says they’d swept the area two minutes earlier. A video from the security camera shows a shadowy, unidentified figure, taking something out of her pocket and dropping it in the area where the slip and fall occurred. Even with those sparse facts, you have the germ of a story. In a sense, lawyers are trained to become storytellers. (And I don’t mean to add the misguided stereotype that attorneys make things up; often, there really are two sides to the story.) Conversely, the law provides raw material for the writer, automatically creating conflict. Lawsuits also create mystery, because the facts are almost always ambiguous—an automatic whodunit.

There’s another reason why writers are drawn to the law and lawyers are drawn to writing—as author-lawyer Daco Auffenorde has pointed out, lawsuits have a classic three-act structure. http://www.usatoday.com/story/happyeverafter/2014/04/22/daco-romance-authors-lawyers/8013569/. The attorney files a complaint and learns about the witnesses (characters) (Act I); conducts depositions and fact investigations, where confrontation occurs (Act II); and resolves the conflict at a trial (Act III). In a sense, trial lawyers live out a drama each time they handle a case. And authors of legal drama have a ready-made structure just waiting to be molded into a novel.

While it’s not the most pleasant part of the job, attorneys also have to become conspiracy theorists. They make judgments about their own client, about the other side, and about the third-party witnesses. Lawyers must ask questions like, “Who’s lying?”

“Who’s self-motivated?” “Who’s ethical?” “Is he nervous?” “Will the jury think her arrogant?” In other words, the lawyer, like the writer, engages in character studies, and the legal system provides ready-made characters for the writer. In my own recent novel, Reckless Disregard, my lead character, attorney Parker Stern, represents a video-game designer known to the world only as Poniard, who’s becomes a defendant in a libel action after accusing a movie mogul of kidnapping an actress twenty-five years prior. Poniard will only communicate with Parker through e-mail, which makes the attorney’s usual “character study” of his client impossible. And this inability to evaluate his own client leads Parker into great danger.

Lastly, our adversarial system of justice assumes that there’s a right side and a wrong side, and where there’s “right and wrong,” there’s a moral judgment to be made. Writers thrive on raising moral questions. Melville’s Billy Budd shows how earthly justice and divine morality sometimes conflict. To Kill A Mockingbird explores personal courage in the face of violent racism. The never-ending lawsuit in Dickens’s Bleak House casts an unjust legal system as the novel’s antagonist.

So lawsuits have all the attributes of a good story—conflict, characters, mystery, and moral ambiguity. That’s why the legal system has provided grist for fiction and why so many lawyers are equipped to become authors.

At least, that’s this lawyer’s story.

If you would like to read more about Robert Rotstein’s books please click here.

Robert Rotstein is a writer and attorney who’s represented many celebrities and all the major motion picture studios. He’s the author of Reckless Disregard (Seventh Street Books, June 3, 2014) about Parker Stern, an L.A.-based attorney, who takes on a dangerous case for a mysterious video game designer against a powerful movie mogul. Reckless Disregard has received starred reviews from Kirkus and Booklist. His debut novel, Corrupt Practices (Seventh Street Books), was published in 2013.

Visit his website at robertrotstein.com

(Have an idea for our blog? Then share it with our Killer Nashville family. With over 24,000 visits monthly to the Killer Nashville website, over 300,000 reached through social media, and a potential outreach of over 22 million per press release, Killer Nashville provides another way for you to reach more people with your message. Send a query to contact@killernashville.com or call us at 615-599-4032. We’d love to hear from you. Thanks to Maria Giordano and author Tom Wood for his volunteer assistance in coordinating our weekly blogs. For more writer resources, visit us at www.KillerNashville.com)

Know your Audience: Writing for Children / Author Charles Suddeth

Adult readers would not be content with a story meant for a child; so it stands to reason, the converse is true. Children don’t give a hoot about what adults are reading. That is, unless, it’s an adult reading to them. In this week’s blog, author Charles Suddeth says, what probably should be said repeatedly and before putting fingers to a keyboard or pen to paper, for whom am I writing? Charles offers some clear and poignant guidelines for those who may consider writing for the younger set. It is tougher than you may realize.

Happy reading!

Clay Stafford,

Founder of Killer Nashville

Know your Audience: Writing for Children

By Charles Suddeth

One of my favorite writing rules is: There are no rules. But I would add: you have to know the rules and your audience before you can break the rules.

I am primarily a children’s writer. I belong to the Society for Children’s Book Writers & Illustrators, or SCBWI, and I host two critique groups: a picture book group and a middle-grade/young adult group. Members often submit manuscripts that either aren’t children’s books or their main character is the wrong age. For an annual contest I sponsor, some of the submissions I receive are poems or short stories with children as the main character, but with adult feelings and observations. I also receive memoirs of an adult looking back at childhood, which is also not what children enjoy reading.

If your interest in writing children’s books, the rule of thumb is that children like to read books with a main character their age or slightly older. Although recommended ages for readers and main characters differ from publisher to publisher, here are a few guidelines you should keep in mind:

Picture Books: Ages 3 to 7, with main character’s ages 5 to 9 (Board Books for younger readers and Easy Readers for slightly older readers will extend this range in both directions).

Middle Grade (Middle Reader’s): Ages 8 to 13, with main character’s ages 10 to 14 (slightly younger readers may read Chapter Books, which are early middle reader’s books with a limited number of illustrations).

Young Adult: Ages 14 to 18; high school readers. Main character’s ages high school freshmen to seniors. (New Adult, Young Adult fiction geared toward college-age readers, is becoming popular).

Two years ago, an adult fantasy anthology published my dark/horror short story about a little boy almost drowning in a well. It didn’t deal with a child’s issues or problems, so I never considered submitting it to children’s publications. Here are the issues the main characters usually deal with for each category:

Picture Books: Searching for Security. Children this age, even while playing and having fun, need to know their parents are there for them with love, protection, and life’s necessities. The Llama Llama series of books by author/illustrator Anna Dewdney is about a baby llama that endures various adventures and challenges, but above all, Mamma must remain nearby. Llama Llama Red Pajama, I believe, was the first book of the best-selling series.

Middle Grade: Searching for Identity. Children in this age are not certain who they are or what their abilities are. They often do things in groups to obtain peer approval, because they lack self-confidence. JK Rowling’s early Harry Potter books are an example. Harry didn’t know he was a wizard with powers or that he would have a quest. And he didn’t know who his allies (his group) would be, but he gradually learned.

Young Adult: Searching for Independence. Teenagers are famous for their rebellion against their parents, sometimes called “attitude.” Psychologists have described this as subconscious psychological efforts to separate themselves from their families so they can become adults with their own families. Most people think of the Hunger Games as pure survival. But it’s more than that. Katniss loses her father, her mother is weakened and out of touch, so she seeks independence from the oppressive, totalitarian society that has crippled her family.

Another peculiarity of writing for children is that boys prefer to read books where the main character is a boy, but girls will read books where the main character is a boy or girl. I don’t believe this applies to adults.

I understand that most of the writers in Killer Nashville are genre writers, but nowadays children’s books come in all genres. This year, 4RV Publishing will release my picture book, Spearfinger, about a Cherokee witch battling a little boy. The story of Spearfinger could have been a horror story, but I adapted it as a picture book for ages 5 to 8.

My other favorite rule for writing is: Take your reader where they are not expecting to go. This rule also applies to children. Once you know your audience you can take them to destinations unknown and even undreamed.

If you would like to read more about Charles Suddeth’s books please click here.

Charles Suddeth was born in Jeffersonville, Indiana, grew up in suburban Detroit, Michigan, and has spent his adult life in Kentucky. He lives alone in Louisville with two cats. His house is a few blocks from Tom Sawyer State Park, where he likes to hike and watch the deer. He graduated from Michigan State University. He belongs to the Society of Children’s Book Writers & Illustrators (SCBWI Midsouth), International Thriller Writers, Green River Writers, and the Kentucky State Poetry Society.

Books: Halloween Kentucky Style, middle readers, Diversion Press, paperback, 2010. Neanderthal Protocol, adult thriller, Musa Publishing, e-book, 2012. 4RV Publishing will release three books: Picture book, 2014, Spearfinger; Young adult thriller, 2014, Experiment 38; Picture book, 2015, Raven Mocker. He moderates two critique groups for children’s writers, and hosts a monthly schmooze (social/networking meeting) for Louisville children’s writers. He is also the Contest Director for Green River Writers’ yearly contest. Visit his website at www.ctsuddeth.com

(Have an idea for our blog? Then share it with our Killer Nashville family. With over 24,000 visits monthly to the Killer Nashville website, over 300,000 reached through social media, and a potential outreach of over 22 million per press release, Killer Nashville provides another way for you to reach more people with your message. Send a query to contact@killernashville.com or call us at 615-599-4032. We’d love to hear from you. Thanks to Maria Giordano and author Tom Wood for his volunteer assistance in coordinating our weekly blogs. For more writer resources, visit us at www.KillerNashville.com)

Creating Emotion on the Page / Author Leslie Budewitz

I’ll never forget the moment when Romeo rides past the well-intentioned Friar Lawrence with that, oh, so important communiqué about Juliet’s poisoned slumber in Franco Zeffirelli’s version of Romeo and Juliet. I wanted to yell at the screen. Even though I knew the story and what was to happen, the depth of despair from that single act of dramatic irony where no words were spoken, said it all. In this week’s blog, author Leslie Budewitz writes about evoking readers’ emotions in much the same way. As writers we don’t say, ‘And now readers, it’s time to be sad, or happy.’ Instead, the reader is guided into understanding the characters and why the actions they commit are destiny. Otherwise, as Leslie, so aptly explains, the readers won’t feel anything!

Happy Reading!

Clay Stafford,

Founder Killer Nashville,

Publisher Killer Nashville Magazine

Creating Emotion on the Page

By Leslie Budewitz

Story lies not in what happens to our characters—whether they lose a spouse, stumble over a body, get sold into slavery—but how they respond to what happens. How events hit them deep inside, touch an old wound, trigger a struggle, lead to more conflict, and ultimately, growth and resolution. The purpose of plot is to force our characters into those challenging situations, where they must confront their internal conflicts, externalizing them in action. This is as true in the cozy mysteries I write as in literary fiction or any other genre. The tone and depth of exploration may vary, but the heart of story remains the same.

But if we tell our readers what our characters feel, they won’t feel anything. We need to evoke emotion by showing how our characters respond to emotional situations. How do they move when struck by grief, annoyed by stupidity, or baffled by absurdity? What happens to their faces, their voices? How do their feelings influence what they say—and how they say it?

First, we can call on our emotional experience. Then, we analogize from our experience to our characters. By analogize—a term lawyers use when comparing cases where the facts differ, but the same legal principles apply—I mean we take what we know, compare it to another situation, and picture what would happen then. I remember clearly how I felt physically and emotionally, and what I did, when a man I didn’t know walked in my unlocked dorm room while I was napping. I can extrapolate from my experience and imagine how my character would respond. (Turned out my intruder was a well-known thief, not a rapist, and didn’t realize my door led to a suite, not a single room, so I wasn’t actually alone.) A character assaulted as a young child, or who had witnessed a brutal attack, would bring to the same intrusion a more complex reaction, based on her own experience.

I used a similar technique in writing Crime Rib, the second in my Food Lovers’ Village Mysteries. My protagonist, Erin Murphy, was 17 when her father was killed in a still-unsolved hit-and run. Now 32, she finds a friend’s lifeless body alongside the road, apparently the victim of a hit-and-run. Ike Hoover, the undersheriff overseeing the investigation, was the deputy in charge of her father’s case, complicating her view of him. As I wondered how Erin would respond to him, I found myself walking around the house, searching mind and body for analogous situations.

I replayed an incident nearly 30 years ago when I took a walk near a golf course, saw a man keel over on the green, and ran for help, struggling to give directions to an unfamiliar place. I remembered watching in a courtroom when an older lawyer clutched his chest, stepped back from the podium mid-argument, and died. And I recalled a collision in front of my house fifteen years ago. The loud crack broke the afternoon. Dashing outside. Seeing a young man stumble toward me. Knowing I had to check his truck, that I couldn’t rely on his dazed assertion that he’d been alone in the cab. Mining my feelings, I realized I was recreating them in my body, all these years later. My jaw tightened, my breath thinned, sounds came at me as if filtered by a fog.

“[Ike] suppressed a smile. I sat and took the statement he handed me. Rereading my description of what I’d seen and heard on Saturday night brought all the sensations crashing back. My breath went shallow, and I felt the anxiety racing through my veins, headed for my heart. I did not want to feel this. I wanted to walk away. My self-righteous words to Kim still echoed in my ears: Stacia deserves justice, too.”

How do we tap into emotions beyond our own pale? Emotional research. I often call on my doctor-husband’s observations of how people respond to stressful situations, emotionally and physically, and the long-term effects. To explore Erin’s reactions, as a teenager and a young woman, to her father’s death, I thought about everyone I knew who’d lost a parent when they were young. Me, at 30, is very different from 17, but a good starting point. My college best friend, at 21; and a high school classmate at 22, who later lost her husband when her son was only 4. A law firm colleague whose father’s death when he was 18 set him on a much-different path than he’d planned. I wrote what I knew of their experiences out by hand to get at the physical experience. To put in my body, so my writer brain could call on it.

I also found online guides for teens who’ve lost a parent and for their teachers. Kids sometimes have a not-quite-rational feeling that something unrelated to their actions must still be their fault, somehow, or that it marks them.

“Calling him by his first name wasn’t disrespect. Undersheriff sounds too much like undertaker to me, and it had been Ike who’d come to the village Playhouse to get me, during rehearsal, after my father’s accident. The association still stuck. Childish, maybe, but it wasn’t a feeling I could logic my way out of.”

A writer friend described her own teenager, a very different girl from Erin, but whose desire for black-and-white answers helped me flesh out Erin’s best friend Kim Caldwell. Now a sheriff’s detective, Kim’s reaction cost both girls their friendship, led to her career in law enforcement, and still plagues her.

“Kim and I had been best friends all through junior high and high school. Until my father died, the winter of senior year. That had been too much for her, and the night of his accident, I lost my best friend, too. Since my return, we’d run into each other a few times, but exchanged only small talk. Why she’d chosen law enforcement remained a mystery. …

Something slid down her left wrist and she shoved it back up her sleeve. A bracelet? A memory flashed across my mental screen and vanished.

“I’m sorry to have to put you through this,” she said. “Your family means a lot to me.”

Right. My family meant so much, she dropped me like a rock when my father died. Like it might be contagious. Like I had done something to her.

I nodded. Until I knew what was going on, I needed to be very careful.”

Only when we dig into our characters’ minds and hearts, their successes and failures, their stresses, dramas, and traumas, will we know how they’ll respond to events on the page. But if we’re willing—even when it brings back up our own painful moments—we can create characters our readers will want to know.

About Crime Rib:

“Gourmet food market owner Erin Murphy is determined to get Jewel Bay, Montana’s scrumptious local fare, some national attention. But her scheme for culinary celebrity goes up in flames when the town’s big break is interrupted by murder…

Food Preneurs, one of the hottest cooking shows on TV, has decided to feature Jewel Bay in an upcoming episode, and everyone in town is preparing for their close-ups, including the crew at the Glacier Mercantile, aka the Merc. Not only is Erin busy remodeling her courtyard into a relaxing dining area, she’s organizing a steak-cooking competition between three of Jewel Bay’s hottest chefs to be featured on the program.

But Erin’s plans get scorched when one of the contending cooks is found dead. With all the drama going on behind the scenes, it’s hard to figure out who didn’t have a motive to off the saucy contestant. Now, to keep the town’s rep from crashing and burning on national television, Erin will have to grill some suspects to smoke out the killer…”

If you would like to read more about Leslie Budewitz’s books please click here.

Leslie Budewitz is the national best-selling author of Death al Dente, first in the Food Lovers’ Village Mysteries, winner of the 2013 Agatha Award for Best First Novel. Crime Rib, the second in the series, was published by Berkley Prime Crime on July 1, 2014.

Also a lawyer, Leslie won the 2011 Agatha Award for Best Nonfiction for Books, Crooks & Counselors: How to Write Accurately About Criminal Law & Courtroom Procedure (Quill Driver Books), making her the first author to win Agatha Awards for both fiction and nonfiction.

For more tales of life in the wilds of northwest Montana, and bonus recipes, visit her website and subscribe to her newsletter. Website: www.LeslieBudewitz.com Facebook: LeslieBudewitzAuthor

(Have an idea for our blog? Then share it with our Killer Nashville family. With over 24,000 visits monthly to the Killer Nashville website, over 300,000 reached through social media, and a potential outreach of over 22 million per press release, Killer Nashville provides another way for you to reach more people with your message. Send a query to contact@killernashville.com or call us at 615-599-4032. We’d love to hear from you. Thanks to Maria Giordano and author Tom Wood for his volunteer assistance in coordinating our weekly blogs. For more writer resources, visit us at www.KillerNashville.com)

On Short Fiction and Evil Masterminds / Author Robert Mangeot

Writing short fiction demands a different kind of mental training. While novels can luxuriate with expansive plots and subplots, short fiction requires jabs and punches. In this week’s Killer Nashville Guest Blog, author Robert Mangeot cleverly tells us how he went from short story unpublished to well-published. And how you can do the same. You simply have to let the masterminds do their job.

Happy Reading!

Clay Stafford

Founder Killer Nashville,

Publisher Killer Nashville Magazine

On Short Fiction and Evil Masterminds

By Robert Mangeot

Inside us crime writer folk lurks an evil mastermind. Sure, some days the evil one may seem quiet, but always deep in our imaginations is a dimly lit chamber, walls blanketed in maps with dragons stalking the margins, a desk piled with jumbled notebooks, a shrouded figure clacking away in mad flourishes at the computer keyboard. Your inner mastermind is planning, planning, planning.

As crime writer folk, it’s likely you consider having your creative dark side pointed out as a compliment. And you should. If short fiction interests you, then unleashing that evil dude or dudette might be your call to adventure.

Flash to me outside a Manhattan bookshop, a gunmetal sky over SoHo, and an April mist slicking the rush hour streets: a perfect night for spying. You read that right. Espionage. Except I had only written a short story about spies, and the honor of it landing in the MWA anthology Ice Cold—which was launched that rain-slicked night at The Mysterious Bookshop—was borne of fruitful collaboration with my inner mastermind.

Killer stories require more than lightning bolts of inspiration. In crime writer-ese, a great short story is like a heist: intricate timetable, tricky execution, ticking clock. The story mastermind must identify and adapt to each and every obstacle in order to pull off the job.

Flashback to 2010. Flush with creativity, I had locked myself away to crank out stories. They stunk, every blessed one of them. I know that now, but in those heady days I fired off submissions, certain of a breakthrough.

Not so much.

Fast-forward through a trial-and-error montage of research, critique and useful rejection, add any Eighties arena pop soundtrack at your discretion. What kept me going was my stretch goal—selling a story to a dream market like MWA or Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. Trust me, back then when I said stretch, it meant hyperextension. Whether or not I would ever get the dream acceptance letter, who knew? The important thing was the reach.

Fast-forward again through more rewrite and rejection to enlightenment. Finally I understood my stories, like heists without a getaway plan, they were never coming together. Characters, setting, plot, everything had to be crafted to bring out a connected whole. Poe—now there was an evil mastermind—called this “unity of effect.”

For that I learned to call on my mastermind, which means I also learned to pay as much attention to how I’m writing as to what I’m writing. After all, one story is just one story. My creative process is how I’ll write more and better. And so I’ve developed brainstorming rituals that summon the mastermind. He arrives feisty, demanding sharper ideas and I rewrite again and again and again. He forces me to slash away at the labor-of-love early drafts and darling sentences. The evil mastermind is editing, editing, editing.

Some key lessons from the inner mastermind about killer short fiction; he is five-fold:

The Brain: Amp up the premise until it is distinctively your own. Premises are infinite. Take risks. Have fun with voices, characters, and ideas. The price of a short story idea falling apart is pretty much zero, and if it improves your writing, I’d call that a success.

The Grease Man: Like tumblers falling in a picked lock, work every element into the connected whole. Subplots are for novels, asides for Shakespeare. Keep a short story slick and elegant.

The Insider: Do the research. Amazing next-level inspiration comes from having the context and interrelationships nailed. Also, before ever submitting somewhere, read several issues first. Know the target market cold, its submission requirements and editorial preferences. This is make-or-break with pro markets. No heist goes off without first casing the joint, right?

The Muscle: Short stories are all about compressed vibrancy. Find the compelling narrative voice that does the heavy lifting, especially with mood and characterization. Edit, edit, edit until the deeper story emerges and the words crackle.

The Getaway Driver: Start the story late, well after a novel version would open. Move quick, hit hard and get out fast, with a thematic roar that echoes long after the last word is read.

Simple, right? We crime writer folk understand simple doesn’t mean easy. But for me, that journey is becoming an adventure. The short story is dead? Feels pretty alive to me.

You know what else is alive? Your mastermind. Alive and hard at work somewhere in there, planning, planning, planning your story of the century.

If you would like to read more about Robert Mangeot’s books please click here.

Robert Mangeot lives in Franklin, Tennessee, with his wife, pair of cats, and a bossy Pomeranian writing partner. His short fiction has won multiple writing contests and appears in various journals and anthologies, including Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine and Mystery Writers of America Presents Ice Cold: Tales of Intrigue from the Cold War. He serves as the Vice-President of Sisters In Crime, Middle Tennessee chapter. Visit his website at robertmangeot.com

(Have an idea for our blog? Then share it with our Killer Nashville family. With over 24,000 visits monthly to the Killer Nashville website, over 300,000 reached through social media, and a potential outreach of over 22 million per press release, Killer Nashville provides another way for you to reach more people with your message. Send a query to contact@killernashville.com or call us at 615-599-4032. We’d love to hear from you. Thanks to Maria Giordano and author Tom Wood for his volunteer assistance in coordinating our weekly blogs. For more writer resources, visit us at www.KillerNashville.com)

The Problem With Reality / Author Warren Bull

The writing process is fraught with pitfalls. Remove the usual suspects like procrastination and lack of time and you still have real limitations. In this week’s blog, author Warren Bull muses about the writing process and how, sometimes, reality is hard to accept.

Happy Reading!

Clay Stafford

Founder Killer Nashville,

Publisher Killer Nashville Magazine

The Problem With Reality

By Warren Bull

During my thirty years as a clinical psychologist, I saw many people who had problems discerning what was and was not real. I assure you those who cannot identify and react to what the great majority of people experience as reality have very difficult and unpleasant life experiences. When your own perceptions betray you, the world is uncertain. Anxiety and depression are frequent reactions to the uncertainty. The use of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs in an attempt to moderate internal states makes sense at some level.

I am fond of reality. I recommend it over all other contenders. As a writer, however, reality presents a number of real limitations. I see other people who have problems with reality. Here are mine:

Realism in writing is hard to achieve. Realistic-sounding dialogue is quite unlike actual dialogue. Court transcripts don’t make fascinating reading. Casual conversation is even less enthralling — full of “ums,” unfinished sentences, clichés, and people talking over each other. It’s important to listen to real conversations, maybe even reading your own writing aloud, to make sure that it flows.

Coincidence is an issue in plotting. As the old saw has it, truth is stranger than fiction. Happenstance is hard to convey believably. As my statistics professor once explained, unlikely events happen much more frequently than people expect. In horse racing, for example, bettors consistently over-estimate the odds the favorite will win. Sadly, even with this knowledge, my professor was no better at picking winners than anyone else. How to eliminate coincidence? Foreshadow. Set the reader up so that when something happens, when they look back, they can see that it was always coming.

Believability is always at issue. Over the years in the course of my work I have known, among others, people who sold drugs at the wholesale level, people who sold their bodies to survive, people convicted of murder, and people who killed other people for money. On most of the occasions when I wrote about these people, the feedback I received was that my writing lacked credibility. Just because something happened, does not mean describing reality accurately will appear factual to readers. The solution to this is to create characters who are real and then pepper them with the unbelievable and memorable.

These are my problems with reality (and a few solutions). What are yours?

If you would like to read more about Warren Bull’s books please click here.

Warren Bull has won a number of awards including Best Short Story of 2006 from the Missouri Writers’ Guild, and The Mysterious Photo Contest in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, January/February 2012. Forty of his published short stories and novels, Abraham Lincoln for the Defense, Heartland, and Murder in the Moonlight are available at http://www.warrenbull.com/kindle_editions.html. Two short story collections, Murder Manhattan Style and Killer Eulogy and Other Stories are available at http://store.untreedreads.com/. He blogs at http://writerswhokill.blogspot.com/. Warren is a lifetime member of Sisters in Crime and an active member of Mystery Writers of America. His website is http://www.warrenbull.com/.

Have an idea for our blog? Then share it with our Killer Nashville family. With over 24,000 visits monthly to the Killer Nashville website, over 300,000 reached through social media, and a potential outreach of over 22 million per press release, Killer Nashville provides another way for you to reach more people with your message. Send a query to contact@killernashville.com or call us at 615-599-4032. We’d love to hear from you. Thanks to Maria Giordano and author Tom Wood for his volunteer assistance in coordinating our weekly blogs. For more writer resources, visit us at www.KillerNashville.com

Variety is the Spice of Writing – But So Is Plausibility / Author Stephen L. Brayton

The beauty of the written word is that real life can be just a jumping off point. Plus, there’s no reason to get bogged down in the same details over and over. In this week’s blog, author Stephen L. Brayton shares how he incorporates variety into his stories and why it’s so important. After all, Brayton’s heroine Mallory Petersen, a taekwondo instructor and private investigator, packs a sidekick worth getting right.

Happy Reading!

Clay Stafford

Founder Killer Nashville,

Publisher Killer Nashville Magazine

Variety is the Spice of Writing – But So Is Plausibility

By Stephen L. Brayton

Since I’m involved in martial arts, I write a series about a character that is a taekwondo school owner as well as a private investigator. Yes, she carries a gun, but she relies on her martial arts skills more often.

I have two challenges in writing this series. First, is to create scenes where my main character, Mallory Petersen, can use her skills, and secondly, is for her to use a variety of those skills.

After all, what fun would it be for the reader if all she ever threw were a couple of punches and a front kick?

So, I’ve adapted my own training into scenes. Yes, punches and front kicks are used, but also round kicks, sweeps, sidekicks, and a variety of weapons such as the long staff and bahng mahng ee, or single stick.

I’ve been able to take some of my favorite exercises and techniques, allowing Mallory to use them in practical situations.

In an upcoming story, she has to execute with skill certain techniques to avoid being killed by an assailant wielding a knife. The situation is dire. She doesn’t have a weapon. She is also in danger of freezing, suffering from withdrawal symptoms, and can’t waste time or else somebody else dies. It’s one of those scenes designed to keep the reader on edge.

But when I create one of these scenes, I have to choreograph the movements. Many times, I’ve mentally written the order of technique-reaction-counter techniques while doing laps around the local high school track. Running, for me, is a great way to free up my mind to think about writing. When I concentrate on a problem within a story, I focus less on how my muscles hurt or that I want to quit after only a few laps.

Back home, I’ll write down the steps in order, then physically work through them, either alone or with a partner. Of course, I’m not actually going to incapacitate my partner, but I am able to get a feel for how the techniques will work. I also get a sense of time, whether the scene runs too quickly or drags and I need to add more material to spice it up a bit.

One area I need to keep in mind is that Mallory is human and feels pain. My writers group has commented on this several times after I’ve read portions of Mallory’s action scenes. This is not like the movies where no one gets hurt, and the heroine fights through any injury with no consequence. Mallory experiences both pain and injury. Sure, she can grit her teeth and still fight on, but she is not Superwoman.

I know I’ve done my job well when I hear comments from readers who say they can follow the movements and know that what I’ve written, and what Mallory has accomplished, actually works.

Creating new scenarios and using the variety of martial arts techniques I know is part of the fun of writing. With that foundation, my imagination can run free to do whatever is necessary to make the scene worth reading.

If you would like to read more about Stephen L. Brayton’s books please click here.

Stephen L. Brayton owns and operates Brayton’s Black Belt Academy in Oskaloosa, Iowa. He is a Fifth Degree Black Belt and certified instructor in The American Taekwondo Association. He began writing as a child; his first short story concerned a true incident about his reactions to discipline. In college, he began a personal journal for a writing class; said journal is ongoing. He was also a reporter for the college newspaper. During his early twenties, while working for a Kewanee, Illinois, radio station, he wrote a fantasy-based story and a trilogy for a comic book. He has written numerous short stories both horror and mystery. His first novel, Night Shadows (Feb. 2011), concerns a Des Moines homicide investigator teaming up with a federal agent to battle creatures from another dimension. His second book, Beta (Oct. 2011) was the debut of Mallory Petersen and her search for a kidnapped girl. In August 2012, the second Mallory Petersen book, Alpha, was published. This time she investigates the murder of her boyfriend. Visit Brayton’s website at http://stephenbrayton.wordpress.com

Have an idea for our blog? Then share it with our Killer Nashville family. With over 24,000 visits monthly to the Killer Nashville website, over 300,000 reached through social media, and a potential outreach of over 22 million per press release, Killer Nashville provides another way for you to reach more people with your message. Send a query to contact@killernashville.com or call us at 615-599-4032. We’d love to hear from you. Thanks to Maria Giordano, Will Chessor, and author Tom Wood for his volunteer assistance in coordinating our weekly blogs. For more writer resources, visit us at www.KillerNashville.com

Writing History Right / Author Michael Tucker

I wish I had a dime every time my mother would say, “Truth is stranger than fiction.” She was right. Look to history, or read today’s newspapers, and you’ll find an abundance of stories where human action seems unfathomable to imagine, whether violent or charitable. In this week’s blog, author Michael Tucker drives home the point that when telling a story set in history, it’s important to get facts right, down to the most specific details. After all, credibility is on the line, and readers are savvy.

Happy Reading!

Clay Stafford

Founder Killer Nashville,

Publisher Killer Nashville Magazine

Writing History Right

By Michael J. Tucker

Weaving actual historical events into the timeline of your story adds realism and color to the narrative and your characters. And it can be a lot of fun if, during your research, you stumble across some little known piece of trivia that causes you to say to yourself, “Gee, I didn’t know that.”

The process starts with selecting a time period. Will your characters be caught up in the Spanish Inquisition, or the Roaring 20’s? Or maybe they’ll be jitterbugging to the “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy of Company B?”

Whatever period you select, you want to get the peripheries right. By peripheries, I mean those little things that surround your characters, but are not necessarily integral to the storyline. What hairstyle should the women in your story have—a bouffant, beehive, or bun? Should your African-American hero have a Jheri Curl, Hi-top fade, Afro, or Dreadlocks? When did men begin wearing earrings, gold necklaces, and open-neck shirts that showed off chest hair thick as Bermuda grass?

If you work music into your novel, be sure the song is period correct. While I was writing Aquarius Falling, a 1964 period story that takes place at a beach resort, I added Otis Redding’s, “Sitting on the Dock of the Bay.” Perfect for the scene. Unfortunately, he didn’t record it until 1967. Luckily I discovered the mistake before publication, and learned a valuable lesson: memory can fail, so do the research.

In Aquarius Falling, my characters were tiptoeing through history; the events surrounded them, but they weren’t part of it. For the second novel of the series, Capricorn’s Collapse, I wanted my characters deeply immersed in the events of the time. I had to look into the future, allow the characters to mature, and find an event with which my protagonist, Tom Delaney, could credibly become involved. It turned out that 1972 was a honeypot of events that yielded delicious ideas.

The year started with a literal bang when the British Army killed twenty-six unarmed civil rights protesters on January 30, in Derry, Northern Ireland, in what is referred to as, Bloody Sunday. On June 17, the break-in at the Democratic Headquarters in the Watergate complex is discovered. The perpetrators are suspected of being connected to the Committee to Re-elect the President, a group with the unfortunate acronym of CREEP. PLO terrorists interrupt the Munich Olympic Games, which results in the murder of eleven Israeli athletes in what is now known as Black September. A plane crash at Chicago’s Midway Airport on December 8, kills Dorothy Hunt, wife of Watergate conspirator, E. Howard Hunt. She is found carrying $10,000 cash.

The challenge here is to put together a plausible story that connects the protagonist to these historic events.

Historical Fiction differs from the genre of Alternative History. In the former, the fictional characters are pulled into the events of the time. Ken Follett’s, The Pillars of the Earth, works through twelfth-century England during the building of a great Gothic cathedral. In Atonement, Ian McEwan leads his readers through a lie told in 1934 that alters forever the lives of two lovers during World War II. Ruta Sepetys’s Between Shades of Gray exposes the oppressive regime of post World War II Soviet Russia in Lithuania.

Alternative History is what it sounds like—history altered. This genre is for those writers who really want to play God. The fictional characters engage in actions that change the outcome of history. One of the most recent applications of this is Stephen King’s 11/22/63, a time-travel effort to thwart the Kennedy assassination. Fatherland, by Robert Harris, offers a take on how the world would look if Hitler had won World War II.

Working historical events into your writing offers the pleasure of learning details that you may have forgotten about or never knew. And it gives you, the writer, the fun of saying, “What if…?”

If you would like to read more about Michael Tucker’s books please visit our website.

Michael J. Tucker is the author of two critically acclaimed novels, Aquarius Falling and Capricorn’s Collapse. He has also published a collection of short stories entitled, The New Neighbor, and a poetry collection, Your Voice Spoke To My Ear. His poem, The Coyote’s Den was included in the Civil War anthology, Filtered Through Time. Visit his website at www.michaeltuckerauthor.com

Have an idea for our blog? Then share it with our Killer Nashville family. With over 24,000 visits monthly to the Killer Nashville website, over 300,000 reached through social media, and a potential outreach of over 22 million per press release, Killer Nashville provides another way for you to reach more people with your message. Send a query to contact@killernashville.com or call us at 615-599-4032. We’d love to hear from you. And, as always, thanks to Maria Giordano, Will Chessor, and author Tom Wood for his volunteer assistance in coordinating our weekly blogs.

Rolling. Speed. Action. Cut! … Darn, Take Two! Rewriting and the Zen of Film / Author Daco Auffenorde

If the thing to remember when purchasing property is location, location, location, then the thing to remember when writing is…well…not writing at all. It’s rewriting.

Citing examples from Stephen King, Ernest Hemingway, Lisa Scottoline, Charlie Chaplin and others, author Daco Auffenorde examines the process of rewriting, the strong case for getting the idea down and then molding it, and how absolutely critical rewriting is to achieving artistic (if not financial) success.

(And just so you know, I rewrote this intro 7 times.)

Happy Reading! And may you never run out of extra paper.

Clay Stafford

Founder Killer Nashville,

Publisher Killer Nashville Magazine

According to a 2010 CNN report, famed actor-director Charlie Chaplin demanded 342 takes just to get actress Virginia Cherrill to mouth the words “flower sir” in the silent film City Lights. Iconic director Stanley Kubrick reputedly reshot one or more scenes in The Shining over a hundred times.

Great film directors like Kubrick and Chaplin are often revered for their willingness to reshoot scenes. So why do writers believe their first draft is a perfect, one-take scene, or if they do recognize the need to rewrite, become paralyzed by the thought? I think it’s because rewriting is not only a blow to the ego, it’s also hard and time-consuming. Unlike a movie director, an author can’t call “Cut” and reshoot the scene immediately. Yet, rewriting is as critical to a good book as the retake is to a successful movie.

Stephen King told The Paris Review (Fall 2006), “Every book is different each time you revise it. Because when you finish the book, you say to yourself, ‘This isn’t what I meant to write at all.’” In 1958, also speaking to The Paris Review, Ernest Hemingway revealed that he rewrote the ending of Farewell to Arms thirty-seven times and the last page thirty-nine times. According to a mid-2012 article in the New York Times, Seán Hemingway discovered after studying the collected works of his grandfather that there were actually forty-seven endings to the novel. The Telegraph added that not only was the story rewritten multiple times, but that Hemingway also compiled a list of alternative titles before he decided on the final.

What this means is that the key time in the writing process—the time when the book takes shape—is in the rewriting. So, how does the reluctant rewriter make sure her book gets the rewrite it deserves?

Take 3 … and action.

Done. The end. I’d finished writing The Scorpio Affair, the sequel to my debut suspense novel, The Libra Affair. I’d proofed it over and over, corrected typos, tinkered with sentences, cut verbiage. It had to be ready to send out to the publisher. But books are meant to be read, so before submitting my manuscript, I shared it with a trusted beta reader, and he suggested that I yell, “Cut!” and reshoot some scenes. I didn’t take his word for it right away. Instead, I put the manuscript away for a while, and then later read it on my own. He was right.

I knew how I wanted The Scorpio Affair to begin and end, and those parts of the book were fine. In between, I’d taken my heroine Jordan Jakes, a CIA covert operative, on a wild ride with lots of action and intrigue. But much of Scorpio was too episodic. Many chapters told exciting, self-contained stories, but didn’t move the plot forward quickly enough. There was only one thing to do—retake. And though at first I found myself frustrated at the daunting task of an entire rewrite, I remembered that most successful authors embrace the rewrite as a fundamental step in crafting a good story. For encouragement, I recalled the King and Hemingway examples, and also this wonderful quote from best-selling author Lisa Scottoline: “They say that great books aren’t written, they’re rewritten, and whoever said that was probably drinking Dunkin’ Donuts coffee, because they’re right.” I bought a dozen doughnuts, brewed some coffee, and started to revise The Scorpio Affair.

But here are the first two lessons about rewriting. If the process doesn’t come naturally to you, first put the manuscript away for awhile. As Neil Gaiman said, “Finish the short story, print it out, then put it in a drawer and write other things. When you’re ready, pick it up and read it, as if you’ve never read it before.” It’s advice that you hear all the time, but it’s difficult to put your baby to bed even for a few weeks. And second, try to find that trusted beta reader, someone who’ll tell you candidly if there’s rewriting to be done.

There are other ways to foster the rewriting process. Writing groups can help immensely, both because you get feedback from an audience—that’s who we write for—and often because you can read your work aloud. I can’t tell you how many times words looked good on the page but have sounded slow and extraneous when read aloud. If you’re not in a writing group, you should still read aloud even if only to yourself. Your ears will tell you if your story has the right rhythm.

A final alternative—there are many good private editors/writing coaches out there. They can be expensive, so not everyone can afford them. But if you’re lucky enough to have some spare change lying around, they can be very helpful, especially in today’s publishing world, where the editorial staff expects ready-to-go manuscripts.

Take 4 … and quiet on the set.

To conclude, I’m going to advise something that might seem inconsistent with the above. In considering how much to rewrite, trust your gut. Don’t rewrite just because someone tells you it should be done. As the artist, only you can decide when your story is ready. The gaffer, grip, production designer, and cinematographer might all have good input, but you’re the director, and the final cut belongs to you.

And that’s a wrap!

If you would like to read more about Daco Auffenorde’s books please click here.

Born at the Naval hospital in Bethesda, Maryland and raised in Wernher von Braun’s Rocket City of Huntsville, Alabama, Daco holds a B.A. and M.A.S. from The University of Alabama in Huntsville and a J.D. from Samford University’s Cumberland School of Law. When not practicing law, she’s encouraging her children to become rocket scientists and writing novels. Daco’s debut novel, The Libra Affair, an international spy thriller with romantic elements, released in April 2013, and was an Amazon #1 Bestseller of Suspense, Romantic Suspense, and Romance in September, 2013. Daco is a member of the International Thriller Writers, Romance Writers of America, Author’s Guild, and the Alabama State Bar. Visit her website at www.authordaco.com

Have an idea for our blog? Then share it with our Killer Nashville family. With over 24,000 visits monthly to the Killer Nashville website, over 300,000 reached through social media, and a potential outreach of over 22 million per press release, Killer Nashville provides another way for you to reach more people with your message. Send a query to contact@killernashville.com or call us at 615-599-4032. We’d love to hear from you. And, as always, thanks to author Tom Wood for his volunteer assistance in coordinating our weekly blogs.

Adding Depth to Your Story / Guest Blogger Philip Cioffari

The bottom line for writing fiction (and I would also say nonfiction) is telling a good story. While Samuel Goldwyn’s advice of “if you’ve got a message, send a telegram” might be true, it defies a long tradition of creating context in crime and thriller fiction. In this week’s blog, author Philip Cioffari outlines his own path for creating relevance of premise in his latest novel Dark Road, Dead End. Using his technique, any story can be taken to a new level of pertinence and—as a result—can resonate to a larger audience, as well as educate and entertain.

Here’s long-time Killer Nashville attendee and instructor, Philip Cioffari.

Happy Reading!

Clay Stafford

Founder Killer Nashville,

Publisher Killer Nashville Magazine

As writers of fiction, our first (and arguably, our only) obligation is to tell a good story, this notion is an extension of the art-for-art’s-sake view of creative expression. In other words, art needs no justification beyond itself. It isn’t required to serve any purpose other than the pleasure it brings. That being said, I’d like to examine for a moment the ways in which good crime fiction can tell a captivating story at the same time it engages the social issues of the time in which it is written.

One might argue that all fiction, including crime fiction engages—in one way or another—the social order of its time. Most visibly, perhaps, it does this by reflecting moral and philosophical values via a character’s thoughts and actions, the choices a character makes to survive in a world which is almost always—in the case of crime fiction—depicted as harsh, fearsome and unforgiving. So man’s conscience is almost inevitably put to the test in any given story. But there is a strain in crime fiction that engages social issues to an even greater degree. I think, for example, of Jaden Terrell’s new novel, River of Glass, with its concern with the horrors of human trafficking, and Stacy Allen’s new novel, Expedition Indigo, which addresses the need for preserving historic artifacts in the public domain rather than for private gain.

In my own case, I’ve long been a supporter of mankind’s conscientious stewardship of our planet and its resources. I wanted to address that issue in my writing and, because I’m a novelist and not an essayist, I wanted to meld my commitment to being a good storyteller with my concern for the environment. My frequent trips over the years to the Florida Everglades provided me with the setting to accomplish that end.

I was appalled to learn that the trade in exotic and endangered species of wildlife is a multi-billion dollar industry. It stands as the world’s third largest organized crime—after narcotics, and arms running. In the state of Florida, it is second only to the illicit trade in narcotics. Despite an international ban on such trafficking, there are many “rogue” nations that do not enforce the ban and that turn a blind eye towards those who violate it. And to be sure, worldwide, there is no shortage of those willing to engage in wildlife poaching and smuggling. One reason for this is the lucrative rewards for such activities—as one U.S. Customs agent put it, “Pound for pound, there is more profit for smugglers in exotic birds [and other wildlife] than there is in cocaine.” Another appeal to the criminal mind is the low risk of being apprehended. This is a consequence of the fact that most customs agencies are understaffed and over-worked and must turn their attention to higher-profile crimes, like the trade in narcotics and guns.

The way the black market system works is this: animals are poached from all over the world, smuggled illegally out of their respective countries, then shipped thousands of miles via land and sea, and ultimately smuggled into the country of destination. The U.S. and China are the two largest consumers of such contraband. But Southeast Asia and Europe are not far behind.

I wanted to shed light on this situation, to call attention to it and—because I’m a writer of fiction—do so in as entertaining a way as possible, hence the noir suspense/thriller format of my new novel, Dark Road, Dead End. My main character is a U.S. Customs Agent in South Florida, investigating a wildlife smuggling operation based in the Everglades, a nefarious network so large it supplies endangered species to pet stores, individual collectors, and roadside zoos across the country, as well as to “reputable” municipal zoos willing to close their eyes to the illegal source of the animals they wish to exhibit. The danger he faces comes, ironically, from both sides of the law.